SANDUSKY, Ohio — All spring and summer, the massive algae bloom in western Lake Erie continued to grow, making its way east to the Lake Erie Islands, Port Clinton and Sandusky. At one point, it was even visible from space.

The bloom in the open lake has dispersed now that it’s fall, but a second algae bloom in Sandusky Bay didn’t go away until early October, according to scientists from Bowling Green State University.

George Bullerjahn, a professor of biology at BGSU, said the bloom in the open lake is caused by a cyanobacterium called Microcystis, which produces a toxin called Microcystin. It’s the toxin that shut down the Toledo water supply in 2014.

“In Sandusky Bay, there’s a different cyanobacterium which blooms and it produces the same toxin, but it behaves very differently,” Bullerjahn said.

That cyanobacterium is called Planktothrix, and according to Bullerjahn, it forms early in the season and persists longer than the Microcystis bloom, which typically happens from July to September.

“We’re looking at an event that starts in mid-May and goes all the way to the beginning of October,” Bullerjahn said of the Planktothrix bloom, noting it sometimes continues until Halloween.

Bullerjahn said he and his team from BGSU are studying Planktothrix because “the environmental drivers of this bloom event are very, very different than what drives the Microcystis bloom.”

In addition, there’s a “long-term restoration effort in the bay, and we have a lot of instruments out here which are monitoring bloom intensity,” Bullerjahn said. “And then as restoration efforts are put in the bay, we can see whether these restoration efforts are actually improving the situation.”

The ultimate goal, Bullerjahn said, is to reduce Planktothrix in the bay, making it safe for recreation and reducing the burden on drinking water treatment plants.

What is Planktothrix?

Bullerjahn said cyanobacteria such as Microcystis and Planktothrix “have been around for three billion years, and they’ve all evolved to adapt to different conditions. You find cyanobacteria everywhere from pole to pole, you find them in desert crusts, you find them in water. Anywhere there’s light, you’ll find cyanobacteria.”

He noted that Planktothrix survives environments with low nitrogen, while Microcystis usually grows in more nitrogen-rich environments. The water in Sandusky Bay can get very stagnant, which Bullerjahn said can lead to processes that “basically eliminate all the nitrogen in the water.”

“Additionally, it’s very well-adapted to low light,” Bullerjahn said. “There’s a lot of sediment in the water here and that dims the light in the water column, and Planktothrix is particularly good at living in nitrogen-depleted dim waters that can be a little cooler, especially in the springtime, than the open lake.”

Asked how Planktothrix affects other fish and vegetation, Bullerjahn said it didn’t affect fish too much.

“One thing that has changed a lot in the bay, just due to land use and so forth, is that a lot of submerged aquatic vegetation which was native to the area is gone,” Bullerjahn said. “And what that does is it yields a lot of sediment being resuspended in the water and that generates actually a pretty good environment for the bloom to persist, and so a lot of restoration efforts are aimed at limiting sediment and actually putting in place aquatic vegetation, which will hold the sediments in place and filter out some of the nutrients.”

Michelle Neudeck, a Ph.D. student in microbiology at BGSU, said that Planktothrix and Microcystis look different in the water.

“They’re structured differently,” Neudeck said. “Microcystis is little round balls and they go through and stick to each other and you get those mats and you get that thick soup of water. Planktothrix is long little threads and so it doesn’t aggregate as much and then you get the clearer green [water].”

Bullerjahn described Microcystis as a surface scum.

“And it is unsightly,” Bullerjahn said. “If you’ve been out there, it’s a really remarkable and horrible-looking thing.”

Still, he said, just because Planktothrix doesn’t look as bad doesn’t mean it’s any less toxic.

“I think maybe you can be given a false sense of security that, ‘OK, the water doesn’t look as bad as it is way out there,’ but you may be dealing with toxin levels that are just as high,” Bullerjahn said.

How they’re researching the organism

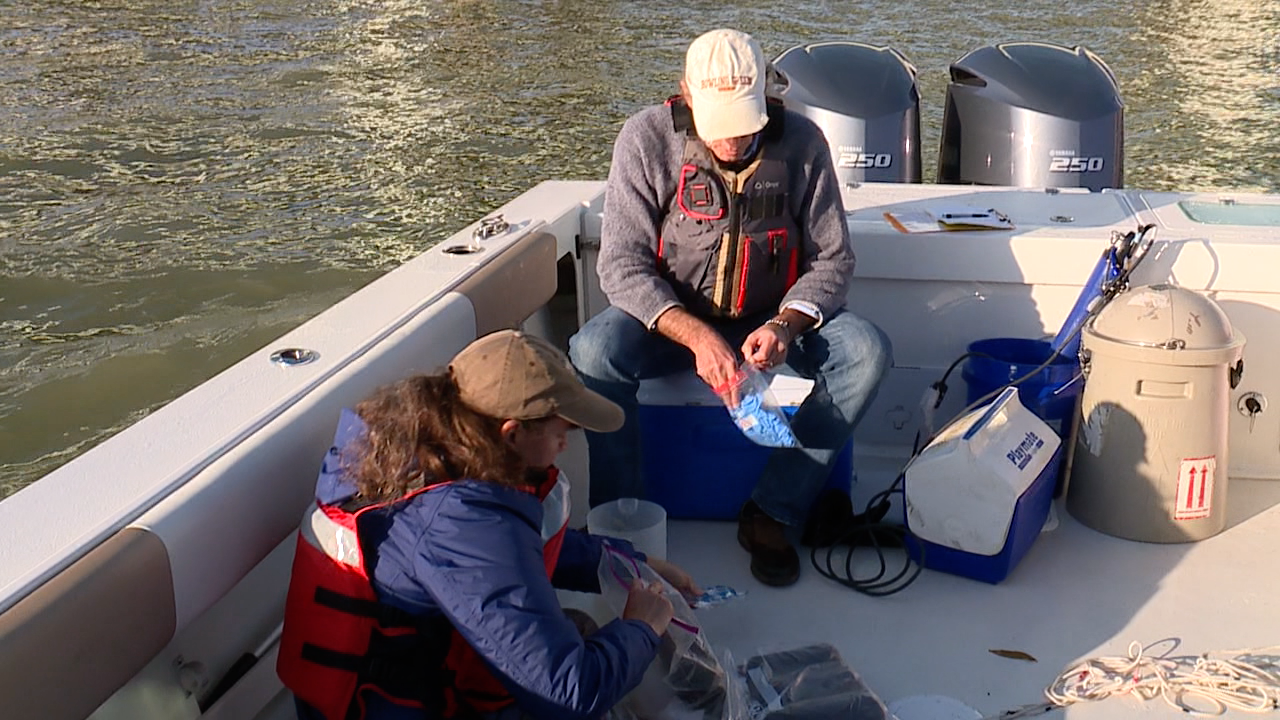

On a day in late October, Bullerjahn and Neudeck collected samples from the water and filtered microbes, flash-freezing them in liquid nitrogen to bring back to the lab to extract DNA and RNA.

“We want to understand sort of what the baseline community is under a non-bloom condition,” Bullerjahn said. “What guys are hanging out when the bloom is gone, are these organisms which are present next spring, do they assist in the bloom, do we see correlations between certain kinds of organisms at different times of the year which may be assisting the bloom or killing it off?”

Along with a company called Limnotech out of Ann Arbor, Bullerjahn’s team is installing sensors and equipment in the bay to collect data. Some of the instruments will stay in place throughout the winter, and some of the data collected will be available to the public in real time.

“It’s going to help assess the success of the restoration efforts to see is sediment really staying in place, is the water becoming less turbid,” Bullerjahn said. “In turn, we can measure how much chlorophyll is in the water as a proxy for how much cyanobacteria is there.”

He said it will also allow the team to assess the bay on a day-to-day basis, if not more often, allowing them to figure out what environmental changes are taking place and what the bloom might look like in the spring.